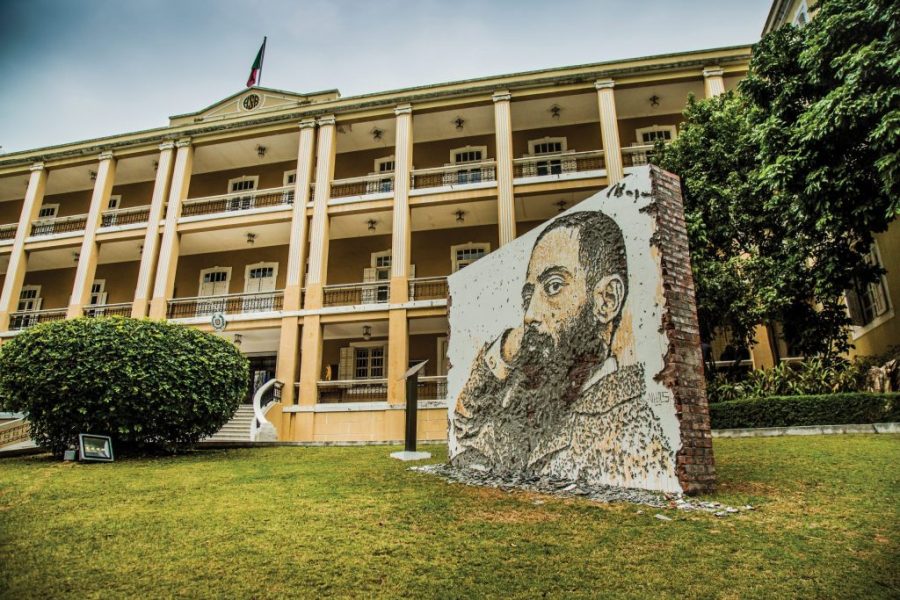

If people associate Macao with any poet at all, it is Luís de Camões — the 16th-century colossus of Portuguese literature and author of what is considered one of the language’s great epics, Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), which he may have partly written while in exile in Macao.

Today, his name lives on in the Camões Garden and Camões Grotto. No such honours, however, have been bestowed on Camilo Pessanha — a poet that Portuguese-language news outlet Ponto Final describes as “completely connected to Macao.”

The two writers couldn’t be more different. Born in Coimbra in 1867, Pessanha is the chief exemplar of Portuguese symbolist poetry. He arrived in Macao in 1894, working variously as a lawyer, judge, journalist, and teacher, with his one published work being Clepsidra (1920). The volume has been updated many times as fragments and other poems by him come to light.

Pessanha died 97 years ago today. The anniversary is unremarked in the city where he spent most of his life. “It’s another year and, unfortunately, there is nothing new,” Alexandra Domingues, a teacher at the Portuguese School of Macau, told Ponto Final. “Camilo Pessanha, to my regret, is forgotten.”

That may partly be because his life was “far from exemplary,” in the eyes of Donald Pittis and Susan J. Henders, the editors of the anthology Macao: Mysterious Decay and Romance.

“An inveterate opium smoker,” they wrote, “he had been attracted to [Macao] by the drug’s plentiful supply. He lived with a succession of local women in the jumble of books, Chinese art and bric-a-brac that engulfed his house.”

Sebastião da Costa, who knew Pessanha, wrote an essay about the poet that appears in the Macao anthology. “One opened the door” of Pessanha’s house, he recalls, “crossed two museum salons, and turned at a right angle to arrive at the room. One lifted the drape and saw, across the yellow screens, the still black beard and those small, luminous eyes of the day-dreamer.”

Christopher Chu, the coauthor with Maggie Hoi of Macau’s Historical Witnesses, is now working on a book on Pessanha in English, hoping to broaden the poet’s appeal to non-Portuguese audiences.

“Pessanha is a landmark,” Chu tells Macao News, pointing out that the poet was “a judge during the 1910 Coloane pirate attack, he was auditor, he was here when Portugal transitioned from a Monarchy to a Republic. He was an eyewitness.”

That makes the poet “fascinating,” Chu says. “The idea [of the book] is to do two things and that’s what makes it tricky: One is to teach the non-Portuguese audience about Pessanha and the second is to get people to know things about the history of Macao that they might not know.”

Hopefully, Chu may succeed in his bid to raise awareness of Macao’s “other poet” in time for Pessanha’s centenary. Not that Pessanha ever craved fame or indeed much else beyond sensual quietude.

“Slumbering repose all day,” the poet wrote in the poem Desires, “In the shade of the palm, the body weary; / I also want, falling asleep, / In fever’s phantoms to see the sea / But always under the blueness of her gaze, / Enveloped in the heat of her gown.”